How to Deliver Real Job Flexibility to a Distributed Workforce

“Flexibility is not a favor,” said Carmen Canales, SVP and chief people officer at Novant Health, a North Carolina-based health care system. “It’s a business requirement.”

Because it’s not a favor, employers should expect reasonable returns. It’s easy for employers to see dollar signs in their eyes when thinking about how much more productive a flexible workforce might be, but that’s not how it works.

Flexibility may beget productivity, but it doesn’t necessarily exponentially increase our capacity to get work done, and employers need to be realistic about the goals they set.

“Realistic expectations are founded on a few things,” said Melissa Versino, VP and head of leadership development at commercial insurance company Zurich North America. “One is having clear goals: What are your expectations that are linked to the organization’s strategic priorities so they know, ‘What am I accountable for?’” The other, she said, is “having clear mechanisms and metrics by which to measure that performance.”

Orazio Mancarella, who is a VP in HR operations at the Pittsburgh-based banking company PNC, recommended “setting up working agreements with your team to make sure that you have to state that ‘Hey, we’re going to be available at these times. If you’re a caregiver and you need to step out at two o’clock to go pick up the kids after school, no big deal. We understand that because we have that working agreement.’” He added that agreeing to respect time zones is important as well.

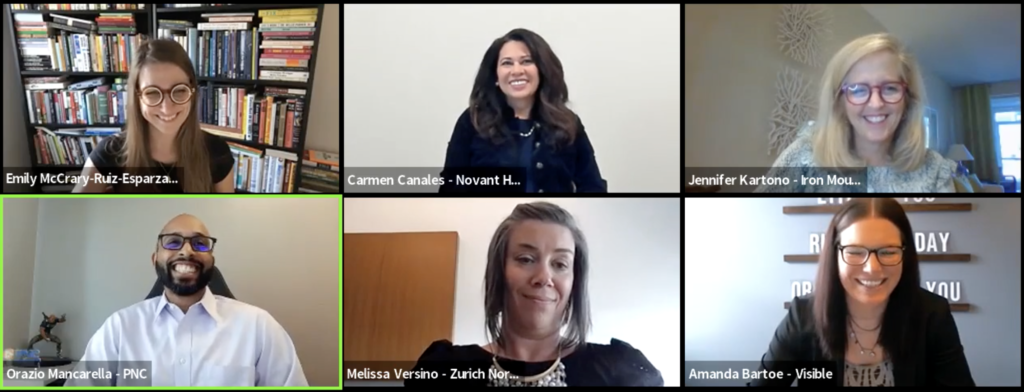

Canales, Versino, and Mancarella spoke on a panel titled “Incorporating Flexibility into the Distributed Workforce,” part of From Day One’s virtual conference this month on Strategies for Communication & Collaboration in the Hybrid Workforce. They were joined by two other people-operations professionals for the conversation, which I moderated.

How flexibility is administered should be tailored to teams rather than whole companies, panelists said.

“We’re a global company in fifty-three countries and with 26,000 people, so we empowered the leaders to try different things and to figure out what worked best,” said Jennifer Kartono. Those leaders focused on what work needs to be done together and started testing flexible schedules with that in mind.”

Kartono is the SVP of people and organizational strategy and culture at Iron Mountain, a data-management company that employs thousands of workers whose jobs must be done on-site. She said theirs was a culture that had to be recalibrated to figure out how to work remotely. “Pre-pandemic, we were really a body-at-work culture,” said Kartono. Everyone was expected to report to the office regardless of their job responsibilities, so at the onset of the pandemic, when the company sent home workers whose jobs could be done remotely, it had to break the body-at-work habit for everyone who didn’t absolutely need to be there.

The recalibration was a success. “We were able to be very innovative, creative, and work in agile ways. As we look at the future, we are moving more toward a flexible work environment for our office workers.” Kartono said.

Amanda Bartoe, the head of operations and future of work at Verizon-owned wireless carrier Visible, saw similar results. “I think our employees were naturally inclined to adapt to new ways of working. In doing so, it’s created a much more tight-knit working environment for people.”

Visible encourages workers to use what the company calls “Me Time,” or time out of the working day to do whatever it is they need to do—take a walk, go to the gym, collect the kids from school. They ask employees to put it on their calendar so everyone can see it. “Everyone knows and respects that time,” said Bartoe. “We put more value in the impact that people are making to the business, versus just crossing that next task off the list.”

For employees whose jobs require them to be on-site, companies can still give them flexibility. “What used to be a set, 12-hour model is now no longer the only option,” Canales said.

Novant Health has what’s called a 9/80 shift, Canales said, “in which an acute-care nurse manager can work 80 hours during a nine-day period, a Baylor program in which you can get a full-time equivalent of a shift in just a weekend. We have options for folks to float from unit to unit, while employed at Novant Health. In other words, they don’t have to leave and join another organization to be able to do that. Many of our clinical teams work three days a week or less, which offers tremendous flexibility, with the hours compressed into those few days.”

Novant also offers remote visits to its patients, so some providers can still see patients without reporting to a facility. “We’re taking advantage of technology and of creativity in shifts so that we can offer the flexibility that our workforce deserves,” Canales said.

Versino recommended staying in touch with those frontline workers to make sure what’s offered really does translate to flexibility. “Help [leaders] understand that some of them are so far removed from that frontline that you may feel there’s flexibility, but your average frontline person would disagree with that.”

Zurich North America, which is based in the Chicago suburb of Schaumburg, Ill., uses its work flexibility to attract Chicago-based talent who don’t want to make the hours-long reverse commute.

Generationally, employees want the same flexibility, said Versino. Why they want it is likely to be different. Someone in their early 40s may have childcare responsibilities, while someone in their early 20s may need to care for a pet. Some employees will be caring for kids, parents, spouses, and pets all at once.

Even for those who don’t need to take advantage of flexibility all the time, that leeway is attractive. “You still get a good response by offering that flexibility,” Mancarella said. “You can get engagement just by having that opportunity. To be able to say ‘I’m not pressured to have to come in if I need time away.’ Or, ‘I’m a little sick, I don’t feel like making the commute, but I can work from home that day.’”

Not everyone wants to work from home. Versino said Zurich’s brand of flexibility caters to that. “Let’s be honest, insurance isn’t the sexiest, most attractive industry, but being able to compete [by having] this gorgeous building in Schaumburg—it’s beautiful. For people who want both, we have this amazing way to say ‘Yes, we also have this way to connect and collaborate.’”

Emily McCrary-Ruiz-Esparza is a freelance writer based in Richmond, Va. She writes about the workplace, DEI, hiring, and issues faced by women. Her work has appeared in the Washington Post, Fast Company, and Food Technology, among others.

The From Day One Newsletter is a monthly roundup of articles, features, and editorials on innovative ways for companies to forge stronger relationships with their employees, customers, and communities.