Beyond Pride Month: Toward Greater LGBTQ Inclusion in Corporate America

In declaring her preferred gender pronouns at the beginning of a recent From Day One panel discussion, Toni D’orsay, PhD, dispensed with the usual earnest format. She said her pronouns are Empress, Your Majesty, and Thank you, May I have Another?, “but I do settle for ‘she’ and ‘her’ for your comfort,” said D'orsay, the director of transgender services for Borrego Health, a health care network based in Southern California. Aside from being an ice-breaker, D’orsay’s approach emphasized that pronouns are not only a personal statement of identity, but a respectful gesture. “It's the simplest thing you can do to make everybody else understand who you are instead of making them decide who you are,” said D'orsay.

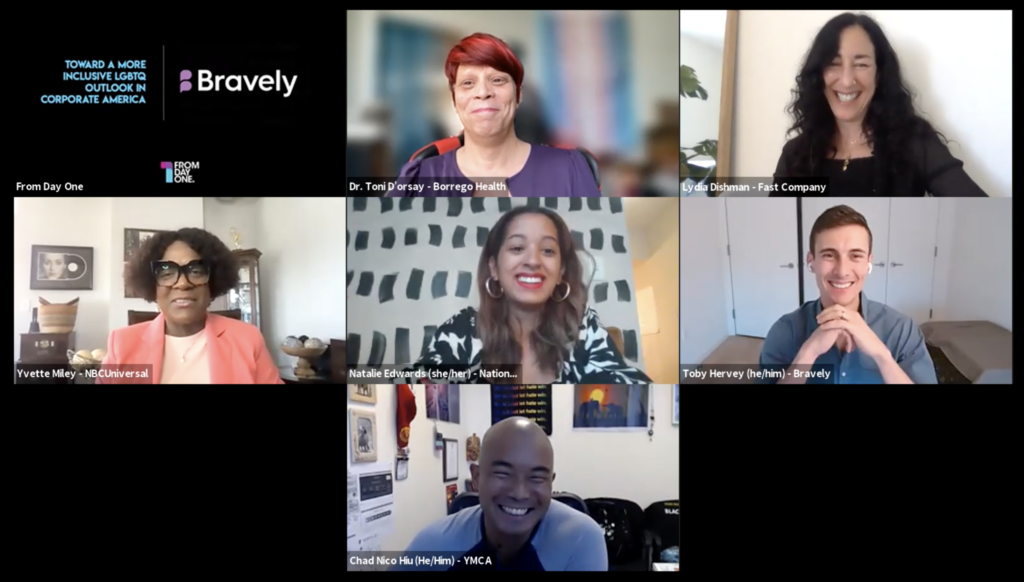

D’orsay made her comments in a recent From Day One webinar titled, “Toward a More Inclusive LGBTQ Outlook in Corporate America,” which looked at how the visibility of LGBTQ employees in the workplace rises during Pride Month in June, yet these workers are still often marginalized when it comes to advancement and career development. It’s a pattern than echoes Women’s History Month and Black History Month. “Everyone has a month in their honor. What you're doing in that month might be your focus. But you should ask yourself, what are you doing the [other] 11 months of the year?” said Yvette Miley, SVP of the NBCUniversal News Group. “What are you doing to make members of that community feel included, heard and seen not just with the parade, or just with cupcakes in the conference room?”

Inclusion runs on parallel tracks–individual, organizational, and societal–and manifests itself at the intersection of symptoms and systems. “We're good at addressing the symptoms; we do that every symbolic month. We're moving from performative into systemic efforts,” said Chad Nico Hiu, SVP for strategy, innovation and impact at the YMCA of San Francisco. Perhaps we should not be overly cynical about the one-month efforts–and ask what comes next. “Sometimes, maybe over-optimistically, we think about some of these performative declarations or statements–or changing your logo for the month of June–as a starting point, the baseline,” said Toby Hervey, CEO and co-founder of Bravely, an employee-coaching platform. “Maybe there are just a lot of organizations that are still in that Phase One.” How to make progress from there?

Focus on Behavior

“If we're honest, the progress of one month can be outweighed by the stall of 11 months,” said Natalie Edwards, chief diversity officer of the energy company National Grid, who adds that people have mostly come around to understanding why diversity matters, but inclusion is one step forward. “Inclusion is a behavior. There's a behavior change that still needs to occur. The system runs based on people's behavior.”

A solution, in her view, is more workshop-based learning, as opposed to the standard lecture system. “We train to change behavior, but the organization has to hold itself accountable,” said Hiu. “What gets measured matters. Diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) training will illuminate what is the thing that we need to address. There are behaviors rooted in beliefs that are acceptable and others that are rooted in beliefs that are not.”

“In order to change those [behaviors], then you have to identify them,” said D'orsay, who singled out four As to be mindful of: Animus, Anxiety, Aversion, and Apathy. “When you combine them with power imbalances, in any kind of relationship, you automatically now begin to understand how you end up with situations such as trans people being murdered, such as the kind of violence that's being engaged against Asian and Black Americans, and the erasure of Indigenous populations,” D'orsay continued. “We're gonna have our little flag, but that's just pink-washing unless we can follow it up with some actual action, as far as I'm concerned.”

DEI training, by itself, often feels perfunctory. “People come from different levels of awareness,” said Bravely’s Hervey. “There's the reality of the forgetting curve. Without the repetitive touch and reinforcement, that touch gets lost.” At Bravely, educational opportunities start with a more traditional training session, which then moves to a group environment where colleagues can process what they’ve learned, and then progresses to more targeted sessions for people to individualize that experience, Hervey said.

Be Mindful of Intersectionality

Edwards singled out an industry-wide issue she described as the “oppression Olympics,” which she described as a kind of competition among marginalized groups. “There's a lot of still sentiment about, What about us? What about me? Why are they getting all the focus right now?” she said. “We have to be honest about how everyone fits into more than one category.”

In this regard, D'orsay brought up the concept of the axis of privilege and oppression. “When you have an axis, you have to have a point on each end. A lot of people don't understand that the two points on each end are stigma and privilege. You cannot talk about one without having to talk about the other,” she said, acknowledging that “when we talk about intersectionality, we tend to confuse them when we're doing the training.” Especially given that individuals can have many layers of identity.

The overlapping categories can create a daunting complexity, especially in moving from concept to action. “I don't know how to fix it. I can't tell you right now,” said Edwards. “But I'm excited for us all to figure that out together as large organizations and even community organizations. How do we make sure that our causes for quality are not in competition with one another, because at the end of the day, you know, divided we fall,” said Edwards.

Be More Accepting of Discomfort

“Comfort is the norm, the standard, the baseline. If you want to be comfortable, it means you want things to not change,” said D'orsay. “I don't feel comfortable anywhere, I don' t trust cisgender people. I don't trust you. If you want to make me feel more comfortable, start feeling uncomfortable. Meet me where I am.”

On that note, it needs to be emphasized that disagreement does not mean disrespect. “We tend to conflate those two things. Discomfort is equated with anger, disrespect. I am uncomfortable on a rollercoaster, but it did not cause me harm,” said Edwards. “Comfort and growth do not coexist. If you go to a training where you are not getting challenged, it means you are not learning anything.”

Be Honest About the Ideal of “Bring Your Whole Self to Work”

At the start of Yvette Miley's career, the concept of showing your full self at work was not a thing. “When you get in, fit in,” was the creed. “Entering the room, I was always trying to calibrate because I was always trying to make sure I didn't offend anyone, that I didn't come across as being the loud Black female, or the angry Black female,” said Miley. “I am from the South. There were no gay people in the South, so I could not be gay. I could not be gay, nor Black. I tried to be a professional, and at some point I thought I am never going to enter a room and not be Black/a woman/and gay. That comes with me. Wherever I go, those layers come with me.” So she came out at work before coming out at home. “I found people at work who didn't judge me, that allowed me to be my full authentic self.”

Yet this awareness has to come with honesty about what's possible. “Unfortunately, the aspirational goal sometimes doesn't work,” said Hiu. “There's nothing wrong in saying we hope to get there, but we're not there yet. I can come to work as a gay man, but there are layers of me I am not comfortable sharing.”

Edwards echoed Hiu's sentiment. “One of my professors said data can tell the truth but not be honest,” she said. “We have to be very honest that the reality is not that you can bring your whole self. You can work towards it, but we like to look forward with rose-colored glasses. We have to keep it real for everyone. Do HR leaders know why LGBTQ people leave the company?"

Look Up Along the Hierarchy

In terms of setting goals, people with authority need to be held accountable. “If you have a diversity officer, in whatever title, the reason you hire them is to have that,” said D'orsay. “If you don't give them power, authority, and data, you hire them and ... why?”

“What are the CEO and business-unit leaders doing? Start with the top. People look up to replicate behavior,” Edwards said. “Then, once it's done, keep moving down. No matter how junior you are, you have to have a DEI performance goal. Culture is not what you say or write, it's what you reward. Look at who gets promoted and how they behave–positively or negatively.” Miley echoed this sentiment: “If you're training everyone, yet the person being phobic is getting the promotion, it's not as much as what you say, but what you do. That says more about your system.”

Angelica Frey is a writer and a translator based in Milan and Brooklyn.

The From Day One Newsletter is a monthly roundup of articles, features, and editorials on innovative ways for companies to forge stronger relationships with their employees, customers, and communities.